This post first appeared on Kineti and is authored by Judah Gabriel Himango, one of Tabernacle of David’s teachers.

I’ve been reading Atomic Habits, a book that’s opened my eyes to how people’s lives are dictated by their habits.

The more good habits you have — eating right, exercising, learning a new language, reading books, writing a journal, etc. — the better your outcomes in life. You’ll be healthier, more mentally sound, financially stable, fit, sociable, interesting, joyful.

Conversely, the more bad habits you have — drinking, smoking, nail biting, fast food, watching porn, binging Netflix, frivolous spending — the worse off you are. Sick, tired, emotionally drained, anxious, empty, depressed, broke.

The book gives a new framing to an old problem of how to kick bad habits and stick to good habits. In it contains a unique lesson for believers. The reframing of this old problem has a life-influencing message for parents. It has broader implications for society. I don’t think the author intended any of those meanings explicitly, yet there they were. I want to pass them on to you in this post, dear Kineti readers.

The old problem every person on earth has faced

First, what is the old problem? It’s, “How can I stop doing [bad thing] and stick to [good thing]?”

How can I stop binge eating and lose weight?

How can I stop wasting so much time on TikTok and instead do something useful with my life?

How can I stop smoking and get good health?

etc.

That’s the old problem.

We have an urge to better ourselves. We have an idea where we’re falling short in life. We try to fix it — lose 20lbs, start eating vegetables every day, cut social media, go to the gym 3 times a week — but these habits quickly fail.

Anecdote: I saw this firsthand a few years ago. When the new year arrived, I resolved to go to the gym once a week. In January, the gym was packed! By February, it was half empty, and by March, it was nearly abandoned. Everyone resolved to do good, but their resolution quickly failed with time.

Reframing the old problem

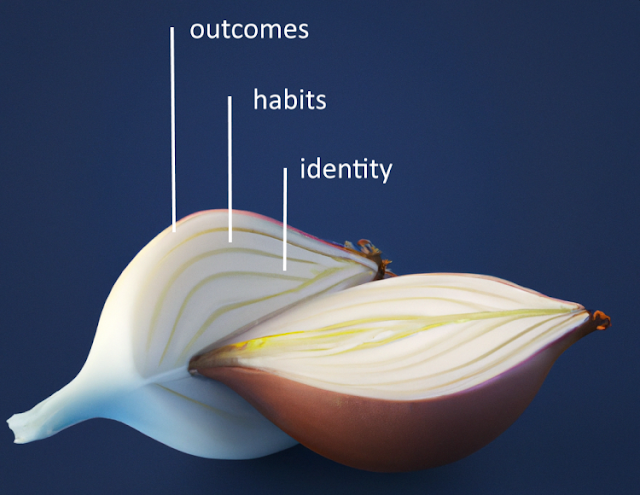

Atomic Habits says the reason our goals often fail is we are too focused on the outcome. Lose 20lbs. Quit smoking. etc. We must reframe the problem to one of identity:

- To change our outcomes, we must first change our habits. One cannot expect to reach a different outcome (lose 20lbs) while living the same way (eating fast food 3x a week).

- Before we can change our habits, we must first change our identity. This keeps you motivated to stick to your new habits.

|

| Atomic Habits shows that a great way to change outcomes is by changing your habits. To effectively change your habits, you change your identity. |

Everybody focuses on the outer layer: outcomes. Stop smoking. Stop drinking. Get fit. Read more. So we start a new habit — go to the gym every week — but we have trouble sticking to good habits and kicking bad ones.

Our habits return to old behavior as our motivation naturally wanes over time. Our resolutions fail and we return to our old ways.

The author explains a key to changing all this is going back another layer: identity.

Who are you? Are you a smoker? Are you a binge eater? A porn watcher? Is that who you are? That’s identity.

Identity is the key to changing your habits and sticking to them.

He refers to several studies for support. One study in particular struck me: a group of smokers who wanted to quit smoking was broken into two groups. The first group was told anytime they were offered a cigarette, they must respond, “No thanks, I’m trying to quit.” The second group was told to respond, “No thanks, I’m not a smoker.”

Can you guess which group did better at quitting?

The group that identified as non-smokers did far better than the first group. Their self-identity changed their habits. “I am not a smoker, so I will not be going on a smoke break. That’s not who I am.“

Want to stop doing X? Be the kind of person who doesn’t do X.

Want to stop being late to everything? Be the kind of person who leaves 15 minutes early. Shape new habits accordingly: set your alarm to leave earlier. Make sure your car has gas before it’s time to leave. Prepare your clothes the night before. Prepare a quick breakfast you can heat and eat in the morning. Best yet, your motivation to stick with these habits will last longer because you’re not the kind of person who’s always late. That’s not you.

As your consistently keep these habits, they go auto-pilot mode: you’ll do them almost without thinking, as routine as getting dressed in the morning. And when you do those habits consistently, you become the person of your identity and your outcomes change. You’re no longer the person who’s always late. Victory.

It’s not magic, but it’s powerful. Identity is powerful. The author gives several such example studies where identity is a major component to changing habits and thus producing better outcomes in life.

I’ve begun to apply these in my own life, with some success:

- I want to read the Bible every morning.

- I want to stop browsing my phone while in bed when I should be sleeping.

- I want to stop scrolling social media in the morning when I need to get up for work.

- I want to stop biting my fingernails.

- I want to learn Hebrew.

- I want to write more (hence this post!)

- I want to practice guitar more.

So, I shape my identity accordingly: I’m the kind of person who takes the Bible seriously. I’m the kind of person who doesn’t miss Hebrew lessons. I’m the kind of person who is serious about improving his guitar skill. Now I’ve been shaping my habits accordingly, and it’s going…good. I think I’ll see some good fruit from all this.

Every time I carry out my habit of Bible reading, Hebrew learning, writing, is a vote for the kind of person I want to be. (And if I miss a lesson, skip reading? Well, that’s a vote in the other direction.)

This key to fixing problems in your life by shaping your identity made me consider the importance of shaping the identity of our kids.

Are you telling your kids they’re stupid? Ugly? Dumb? “Clearly not a math major!” Suck at science? Calling them names when they do bad stuff? Swearing at them? This reinforces a negative identity in them at a time when their identity is in its earliest, most pliable stage. That identity sticks with them for life, friends.

There’s a lesson to parents in there. I’ll cover this in Part II soon.

Thanks for reading, folks.