Editor’s note: This post originally appeared on Think Apologetics. Tabernacle of David considers this resource trustworthy and Biblically sound.

.

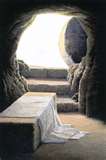

As historians evaluate the sources available for the resurrection of Jesus, a critical question is the dating of the sources. In relation to early testimony, historian David Hacket Fisher says, “An historian must not merely provide good relevant evidence but the best relevant evidence. And the best relevant evidence, all things being equal, is evidence which is most nearly immediate to the event itself.” (1) One key in examining the early sources for the life of Christ is to take into account the Jewish culture in which they were birthed. As Paul Barnett notes, “The milieu of early Christianity in which Paul’s letters and the Gospels were written was ‘rabbinic.’” (2)

Given the emphasis on education in the synagogue, the home, and the elementary school, it is not surprising that it was possible for the Jewish people to recount large quantities of material that was even far greater than the Gospels themselves.

Jesus was a called a “Rabbi” (Matt. 8:19; 9:11; 12:38; Mk. 4:38; 5:35; 9:17; 10:17, 20; 12:14, 19, 32; Lk. 19:39; Jn. 1:38; 3:2), which means “master” or “teacher.” There are several terms that can be seen that as part of the rabbinic terminology of that day. His disciples had “come” to him, “followed after” him, “learned from” him, “taken his yoke upon” them (Mt. 11:28-30; Mk 1). (3)

Therefore, it appears that the Gospel was first spread in the form of oral creeds and hymns (Luke 24:34; Acts 2:22-24, 30-32; 3:13-15; 4:10-12; 5:29-32; 10:39-41; 13:37-39; Rom. 1:3-4; 4:25; 10:9; 1 Cor. 11:23ff.;15:3-8; Phil. 26-11; 1 Tim.2:6; 3:16; 6:13; 2 Tim. 2:8;1 Peter 3:18; 1 John 4:2).

There was tremendous care in ‘delivering’ the traditions that had been received. Jesus’ use of parallelism, rhythm and rhyme, alliterations, and assonance enabled Jesus’ words not only ‘memorizable’ but easy to preserve. (4) Even Paul, a very competent rabbi was trained at the rabbinic academy called the House of Hillel by ‘Gamaliel,’ a key rabbinic leader and member of the Sanhedrin. It can be observed that the New Testament authors employ oral tradition terminology such as “delivering,” “receiving,” “passing on” “learning,” “guarding,” the traditional teaching. Just look at the following passages:

Romans 16: 17: “Now I urge you, brethren, keep your eye on those who cause dissensions and hindrances contrary to the teaching which you learned, and turn away from them.”

1 Corinthians 11:23: “For I received from the Lord that which I also delivered to you, that the Lord Jesus in the night in which He was betrayed took bread.”

Philippians 4:9: “The things you have learned and received and heardand seen in me, practice these things, and the God of peace will be with you.”

2 Thessalonians 2:15: “So then, brethren, stand firm and hold to the traditions which you were taught, whether by word of mouth or by letter from us.”

1 Corinthians 15: 3-7: The Earliest Account

Paul applies this terminology in 1 Corinthians 15: 3-7 which is one of the earliest records for the historical content of the Gospel – the death and resurrection of Jesus. The late Orthodox Jewish scholar Pinchas Lapide was so impressed by the creed of 1 Cor. 15, that he concluded that this “formula of faith may be considered as a statement of eyewitnesses.” (5)

Paul’s usage of the rabbinic terminology “passed on” and “received” is seen in the creed of 1 Cor. 15:3-8:

“For what I received I passed on to you as of first importance: that Christ died for our sins according to the Scriptures, that he was buried, that he was raised on the third day according to the Scriptures, and that he appeared to Peter, and then to the Twelve. After that, he appeared to more than five hundred of the brothers at the same time, most of whom are still living, though some have fallen asleep. Then he appeared to James, then to all the apostles, and last of all he appeared to me also, as to one abnormally born.”

Rainer Riesner says the following about the creed:

To the troubled church of Corinth, Paul, around 54 CE, wrote: I would remind you, brothers [including sisters], of the gospel [euangelion] that I proclaimed to you, which you received [parelabete], in which you also stand, through which also you are being saved, if you hold to the wording [tini logō] in which I proclaimed it to you. . . . For I handed down [paredōka] to you under the first things what also I have received [parelabon]. (1 Cor. 15:1–3) Then the apostle cites a series of statements, a technique he knew from his rabbinical training, indicating certain traditions about Jesus’s death, burial, and resurrection appearances (1 Cor. 15:3–7). There are some important things to be noted. Paul could call a summary of the last part of Jesus’s life euangelion. The apostle reminds the Corinthians that at the foundation of the community (around 50 CE), he taught them some Jesus traditions as part of “the first things.” This is confirmed by 1 Corinthians 11:23–24: “I received [parelabon] from the Lord what I also handed down [paredōka] to you”; then Paul cites the eucharistic words of Jesus in a form independent from, but very near to, the Lukan version (Luke 22:19–20). The formulation “from the Lord” (apo tou kyriou) points back to Jesus as the originator of the tradition (1 Cor. 11:23). Paul is silent concerning those functioning as intermediaries from whom he received the eucharistic words; but 1 Corinthians 15:5–7 shows that the Jesus tradition was connected with known persons such as Peter, James, and the Twelve. Obviously it was not an anonymous tradition. The nearest philological parallel to the Greek words paralambanō (to receive) and paradidōmi (to hand down) are the Hebrew technical terms qibbel and masar, denoting a cultivated oral tradition (m. Abot 1:1). This is in agreement with Paul’s insistence on the “wording” (1 Cor. 15:2) of the catechetical formula in 1 Corinthians 15:3–5. In addition, the strong verbal agreements between the Pauline and the Lukan forms of the eucharistic words point to a cultivated tradition. (6)

There is an interesting parallel to Paul’s statement in 1 Cor. 15:3-8 in the works of Josephus. Josephus says the following about the Pharisees.

“I want to explain here that the Pharisees passed on to the people certain ordinances from a succession of fathers, which are not written down in the law of Moses. For this reason the party of the Sadducees dismisses these ordinances, averaging that one need only recognize the written ordinances, whereas those from the tradition of the fathers need not be observed.” (7)

As Richard Bauckham notes, “the important point for our purposes is that Josephus uses the language of “passing on” tradition for the transmission from one teacher to another and also for the transmission from the Pharisees to the people.”(8)

Bauckham notes in his book Jesus and the Eyewitnesses: The Gospels as Eyewitness Testimony that the Greek word for “eyewitness” (autoptai), does not have forensic meaning, and in that sense the English word “eyewitnesses” with its suggestion of a metaphor from the law courts, is a little misleading. The autoptai are simply firsthand observers of those events. Bauckham has followed the work of Samuel Byrskog in arguing that while the Gospels though in some ways are a very distinctive form of historiography, they share broadly in the attitude to eyewitness testimony that was common among historians in the Greco-Roman period. These historians valued above all reports of firsthand experience of the events they recounted.

Best of all was for the historian to have been himself a participant in the events (direct autopsy). Failing that (and no historian was present at all the events he need to recount, not least because some would be simultaneous), they sought informants who could speak from firsthand knowledge and whom they could interview (indirect autopsy).” In other words, Byrskog defines “autopsy,” as a visual means of gathering data about a certain object and can include means that are either direct (being an eyewitness) or indirect (access to eyewitnesses).

Byrskog also claims that such autopsy is arguably used by Paul (1 Cor.9:1; 15:5–8; Gal. 1:16), Luke (Acts 1:21–22; 10:39–41) and John (19:35; 21:24; 1 John 1:1–4).

As just mentioned, the word “received” παραλαμβάνω (a rabbinical term) means to receive something transmitted from someone else, which could be by an oral transmission or from others from whom the tradition proceeds. This entails that Paul received this information from someone else at an even an earlier date.

As Gary Habermas notes, “Even critical scholars usually agree that it has an exceptionally early origin.” Ulrich Wilckens declares that this creed “indubitably goes back to the oldest phase of all in the history of primitive Christianity.” (9) Joachim Jeremias calls it “the earliest tradition of all.” (10) Even the non-Christian scholar Gerd Ludemann says that “I do insist that the discovery of pre-Pauline confessional foundations is one of the great achievements in the New Testament scholarship.” (11)

The majority of scholars who comment think that Paul probably received this information about three years after his conversion, which probably occurred from one to four years after the crucifixion. While we can’t be dogmatic about this, we do know at that time, Paul visited Jerusalem to speak with Peter and James, each of whom are included in the list of Jesus’ appearances (1 Cor. 15:5, 7; Gal. 1:18–19). This places it at roughly A.D. 32–38. Even the co-founder Jesus Seminar member John Dominic Crossan, writes:

“Paul wrote to the Corinthians from Ephesus in the early 50s C.E. But he says in 1 Corinthians 15:3 that “I handed on to you as of first importance which I in turn received.” The most likely source and time for his reception of that tradition would have been Jerusalem in the early 30s when, according to Galatians 1:18, he “went up to Jerusalem to visit Cephas [Peter] and stayed with him fifteen days” (12).

E.P. Sanders also says:

Paul’s letters were written earlier than the gospels, and so his reference to the Twelve is the earliest evidence. It comes in a passage that he repeats as ‘tradition’, and is thus to be traced back to the earliest days of the movement. In 1 Corinthians 15 he gives the list of resurrection appearances that had been handed down to him. (13)

And Crossan’s partner Robert Funk says:

The conviction that Jesus had risen from the dead had already taken root by the time Paul was converted about 33 C.E. On the assumption that Jesus died about 30 C.E., the time for development was thus two or three years at most.” — Robert Funk co-founder of the Jesus Seminar.(14)

This means that Paul received this information from someone else at an even earlier date. How can we know where he received it? There are three possibilities:

- In Damascus from Ananias about AD 34

- In Jerusalem about AD 36/37

- In Antioch about AD 47

One of the clues as to where Paul got his information, is that, within the creed, he calls Peter by his Aramaic name, Cephas. Hence, it seems likely that he received this information in either Galilee or Judea, one of the two places where people spoke Aramaic. Therefore, Paul possibly received the oral history of 1 Cor. 15:3-7 during his visit to Jerusalem.

In Galatians 1:18 Paul says, Then three years later I went up to Jerusalem to become acquainted with Cephas, and stayed with him fifteen days. Here, “acquainted” happens to derive from a Greek word (historesai) that means “inquire into” or “become acquainted.” (15) Interestingly enough, the word “history” also derives from the Greek word “historesai.” So, the work of the historian is to find sources of information, to evaluate their reliability, to make disciplined “inquiry” into their meaning and with imagination to reconstruct what happened. (16) Paul’s first trip to Jerusalem is usually dated about AD 35 or 36.

Why does this matter?

I was once talking to a Muslim about the dating of the Qur’an and the New Testament. Islam states Jesus was never crucified, and therefore, never risen. The Qur’an was written some six hundred years after the life of Jesus which makes it a much later source of information than the New Testament. It seems the evidence that has just been discussed tells us that the historical content of the Gospel (Jesus’ death and resurrection) was circulating very early among the Christian community. As I just said, historians look for the records that are closest to the date of event. Given the early date of 1 Cor. 15: 3-8, it is quite evident that this document is a more reliable resource than the Qur’an. Furthermore, to say the story of Jesus was something that was “made up” much later contradicts the evidence just presented.

Note: Here is a resource that responds to some Jesus Mythers (e.g., the usual list that includes Robert Price), who attempt to say 1 Cor 15: 3-11 is an interpolation.

Sources:

1. Hacket Fisher, D.H., Historians’ Fallacies: Toward a Logic of Historical Thought (New York: Harper Torchbooks. 1970), 62.

2. Barnett, P.W., Jesus and the Logic of History (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press. 1997), 138.

3. Ibid.

4. Ibid.

5. Lapide, P.E., The Resurrection of Jesus: A Jewish Perspective (Minneapolis: Ausburg 1983), 98-99.

6. Porter, S.E., and Dyer, B.R., The Synoptic Problem, Four Views (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2016), Kindle Locations, 2052-2062

7. Bauckham, R. Jesus and the Gospels: The Gospels as Eyewitness Testimony (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans Publishing Company) 2006.

8. Ibid.

9. Wilckens, U., Resurrection, trans. A. M. Stewart (Edinburgh: St. Andrew. 1977), 2

10. Jeremias, J. New Testament Theology: The Proclamation of Jesus, trans. John Bowden (New York: Scribner’s. 1971), 306.

11. Ludemann, G, The Resurrection of Jesus Christ: A Historical Inquiry (Amherst, NY: Promethus, 2004), 37.

12. Crossan, J.D. & Jonathan L. Reed. Excavating Jesus: Beneath the Stones, Behind the Texts (New York: Harper. 2001), 254.

13. Sanders, E.P.,The Historical Figure of Jesus (New York: Penguin Books), 1993

14. Hoover, R.W., and the Jesus Seminar, The Acts of Jesus,What Did Jesus Really Do? ( Farmington, Minnesota: Polebridge Press, 1996),

466.

15. Jones, T.P., Misquoting Truth: A Guide to the Fallacies of Bart Ehrman’s Misquoting Jesus (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press. 2007), 89-94.

16. Ibid.