Editor’s note: This post originally appeared on Think Apologetics. Tabernacle of David considers this resource trustworthy and Biblically sound.

.

![Christianity In Jewish Terms (Radical Traditions (Paperback)) by [Frymer-kensky, Tikva, Novak, David, Ochs, Peter, Sandmel, David, Singer, Michael]](https://images-na.ssl-images-amazon.com/images/I/4191-u4OqkL._SY346_.jpg)

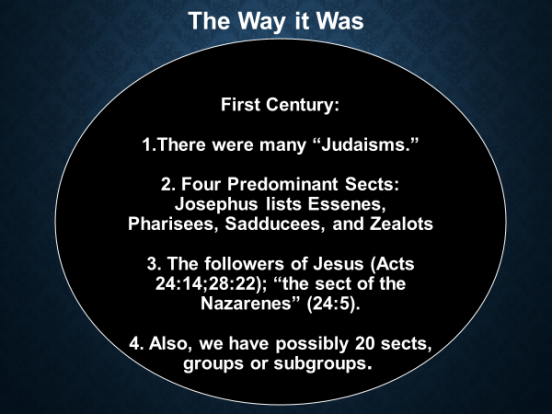

Any discussion of the dialogue between Jews and Christians in the twenty-first century can’t overlook the fact that at the time of Jesus there wasn’t there wasn’t one Judaism. Rather, in the first century, there were four dominant Judaisms—the Sadducees, Pharisees, the Zealots, and the Essenes as well as possibly 20 groups or subgroups. But there was another Jewish sect that arose at this time known as the “Way.” [1] Paul is seen as the ringleader of this Jewish sect which is called “the sect of the Nazarenes.” [2]

In regard to the various Jewish sects mentioned above, two of these sects have survived: Pharisaical Judaism evolved into what is called Rabbinic Judaism and through a series of complex factors, the Nazarene sect eventually became known as a separate faith outside of the Jewish world.

Michael Kruger discusses some of these issues in his book Christianity at the Crossroads: How the Second Century Shaped the Future of the Church. [3] We should also note that what is called Messianic Judaism is nothing new. Messianic Judaism pertains to those who are Jewish and have come to faith in the promised Messiah of Israel. Hence, Jewish believers who practice their faith in a Jewish context are in continuity with the first followers of Jesus.[4]

When I have asked Christians who is the founder of Christianity I receive a look of dismay. After all, didn’t Jesus, a Jewish Torah teacher, break decisively with the foundations of Judaism and all of its institutions such as the Temple, the covenants, the Jewish festivals and the Sabbath and start a new religion called “Christianity?” Unfortunately, this is an anachronistic reading of the Bible. Did Jesus have anything in common with the Judaisms that were previously mentioned? James Charlesworth says:

Was Jesus an Essene, Pharisee, Zealot, or Sadducee? This question also is now exposed as uninformed. Jesus was certainly no Zealot or Sadducee. He was close in many ways to the Essenes and especially some Pharisees; but he was neither an Essene nor a Pharisee. Jesus was influenced by some Essene ideas and many Pharisaic thoughts, but he was not an Essene or Pharisee—let alone a Zealot or Sadducee. He was unique and gave rise to a new Jewish sect.[5]

So if Jesus didn’t come into the world to start a new religion called “Christianity,” perhaps Paul the Pharisee, was the real founder of Christianity? We should note that Paul never refers to himself as a Christian. Even James Dunn says the following:

Prior to Paul what we now call ‘Christianity’ was no more than a messianic sect within first-century Judaism, or better, within Second Temple Judaism — ‘the sect of the Nazarenes’ (Acts 24.5), the followers of ‘the Way’ (that is, presumably, the way shown by Jesus) [6]

![Paul within Judaism: Restoring the First-Century Context to the Apostle by [Mark D. Nanos]](https://images-na.ssl-images-amazon.com/images/I/413PpIl8nRL.jpg)

![Paul the Jew: Rereading the Apostle as a Figure of Second Temple Judaism by [Boccaccini, Gabriele]](https://images-na.ssl-images-amazon.com/images/I/51QoHiVprGL._SY346_.jpg)

To expand on this, Paul offers no evidence that he had ever heard of “Christianity.” “Christianos” ( from the New Testament Greek word is Christos, from which we get the English word “Christ”),occurs only three times [7] which postdate Paul. To say Jesus is the “Christ” means we believe we are saying we agree that he is the “Mashiach”— “the Anointed One” that is talked about in the Tanakh. Granted, “christianoi” could be translated as “messianics.” Thus, we are embracing the Jewish Messiah. Even if there was a movement called “Christianity” that Paul knew of, it was movement that was part of the Jewish world. Thus, it wasn’t seen as something outside of the Jewish world. Regarding what happened to Paul, he more likely received a “call” rather than a conversion to a new religion. He says “ I am a Jew” (Acts 22;3) “I am a Pharisee” (Acts 23;6), and “I am a prisoner for the sake of the hope of Israel” (Acts 28:20). Notice that Paul didn’t say “I was a Pharisee” or that “I was a Jew.” He saw his calling as being in line with the same divine mission that was given to the prophets of the Tanakh.

A survey of the book of Acts should alert us to the fact that the early followers of Jesus remained very Jewish. We see they continued to go to the Temple (Acts 2:46; 3:1; 5:20-21) and synagogue (Acts 13:14-15; 14:1; 17:1, 10; 18:4, 19; 19:8). Even though their Messiah had come, they continued to observe the feasts and the Torah (Acts 20:6; 21:24).

There is no doubt that most modern Christians and Jews as well think Christianity is not Judaism and Judaism is not Christianity. But in most cases, both sides are unaware of the factors that led to this thinking. The “partings of the ways” or the “divorce” between Judaism and Christianity is heavily debated among scholars. To say we can pinpoint an exact time period when Christianity is seen as a separate faith from its Jewish origins is an ongoing debate. There has been more than enough written on this topic.[8] But for now, I will offer a couple of quotes from New Testament scholar Craig Evans:

Did Jesus intend to found the Christian church? This interesting question can be answered in the affirmative and in the negative. It depends on what precisely is being asked. If by church one means an organization and a people that stand outside of Israel, then the answer is no. If by a community of disciples committed to the restoration of Israel and the conversion and instruction of the Gentiles, then the answer is yes. . . . Jesus did not wish to lead his disciples out of Israel, but to train followers who will lead Israel, who will bring renewal to Israel, and who will instruct Gentiles in the way of the Lord. Jesus longed for the fulfillment of the promises and the prophecies, a fulfillment that would bless Israel and the nations alike.[9]

Evans goes onto say:

But we must ask if Paul has created a new institution, a new organization, something that stands over against Israel, something that Jesus himself never anticipated. From time to time learned tomes and popular books have asserted that the Christian church is largely Paul’s creation, that Jesus himself never intended for such a thing to emerge. Frankly, I think the hypothesis of Paul as creator of the church or inventor of Christianity is too simplistic. A solution that is fairer to the sources, both Christian and Jewish, is more complicated.[10]

A few things that stand out: First, what does Evans mean when he says Jesus desired to lead his disciples to bring renewal to Israel? While scholars have written on this topic [11] from my experience, most Christians have very little understanding about the relationship between Jesus and Israel.

This is because Jesus is viewed as the Savior of all humanity. After all, Jesus sent his disciples not just to Israel but to the entire world (Matt 28: 19). So, while at one point in history, because God used the particular (Israel) to bring blessing to the universal (the world) this can lead one to assume once God moved on to the universal (i.e., the ekklēsia”) he is done with the particular. Though Israel was called to be a light to the nations and Jesus is their ideal representative, during His time on earth Jesus seemed to regulate missionary activity to Israel alone. Early on in His ministry, Jesus called the Twelve to dramatize Israel’s reconstitution, and the apostles are sent only to Israel.[12] As Michael Goheen says “It is first of all “a matter of winning Israel for the Gospel; and then Israel, believing, would become a light to the nations.” Thus Jesus’s “apparent particularism is an expression of his universalism—it is because his mission concerns the whole world that he comes to Israel.” [13]

David Stern also provides some helpful reminders as to the Jewish backgrounds of some of the key tenants of our faith:

For years all the disciples of Yeshua (Jesus) were Jewish. The New Testament was entirely written by Jews (Luke being, in all likelihood, a Jewish proselyte). The very concept of a Messiah is nothing but Jewish. Finally, Yeshua himself was Jewish—was then and apparently is still, since nowhere does Scripture say or suggest that he has ceased to be a Jew. It was Jews who brought the Gospel to Gentiles. Paul, the chief emissary to the Gentiles was an observant Jew all his life. Indeed, the main issue in the early Church was whether without undergoing complete conversion to Judaism a Gentile could be a Christian at all. The Messiah’s vicarious atonement is rooted in the Jewish sacrificial system; the Lord’s Supper is rooted in the Jewish Passover traditions; baptism is a Jewish practice; and indeed the entire New Testament is built on the Hebrew Bible, with its prophecies and its promise of a New Covenant, so that the New testament without the Old is as impossible as the second floor of a house without the first. [14]

Conclusion:

We can conclude with James Charlesworth when he says:

Jesus’ group must not be left out of a description of Second Temple Judaism. Jesus and the Palestinian Jesus Movement belong within Judaism. Among the most important insights we obtain from this observation is that we should avoid the term Christian when describing first-century sociology and history.[15]

So if Jesus lead a reform movement within Judaism, what does this mean? Does this mean he is not the founder of Christianity? Most Christians are part of an of an ecclesiastical tradition that evolved much later than the Second Temple period. It is very tempting to read these traditions back into the Bible and make Jesus into our own image. Perhaps we forget the power of paradigms. We see the world and our faith through our existing paradigms. Paradigms are taught to us through tradition, personal experience, teachers, and family. It doesn’t mean all paradigms are wrong. But it can be healthy thing to examine our existing paradigms and ask if they are correct.

Sources:

[1] Acts 9:2; 22:4; 24:14, 22; cf. 24:5.

[2] Acts 24:5.

[3] See Michael Kruger, Christianity at the Crossroads: How the Second Century Shaped the Future of the Church (Downers Grove IL: IVP Academic. 2018).

[4] See D.J. Rudolph and J. Willitts, Introduction to Messianic Judaism: Its Ecclesial Context and Biblical Foundations (Grand Rapids. MI: Zonderban. 2013).

[5] J. H. Charlesworth, The Historical Jesus: An Essential Guide (Essential Guides) (Nashville: Abingdon Press. 2008), 45.

[6] James Dunn, Jesus, Paul and the Gospels (Grand Rapids, Eerdmans. 2011), 119.

[7] Acts 11:26; 26:28; 1 Peter 4:16.

[8] See A. Becker, and A.Y. Reed, eds, The Ways That Never Parted (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck 2003); H. Shanks, ed. Partings: How Judaism and Christianity Became Two (Washington, D.C.: Biblical Archeology Society, 2013); O. Skarsaune, and R. Halvik, eds. The Early Christian Centuries: Jewish Believers in Jesus (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 2007); Michael Kruger, Christianity at the Crossroads: How the Second Century Shaped the Future of the Church (Downers Grove IL: IVP Academic. 2018.

[9] C.A. Evans, From Jesus to the Church: The First Christian Generation (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2014), 18.

[10] Ibid, 33.

[11] See N.R. Brown, For the Nation: Jesus, the Restoration of Israel and Articulating a Christian Ethic of Territorial Governance (Eugene, OR: Pickwick Publications, 2016); S. McKnight, A New Vision for Israel: The Teachings of Jesus in National Context (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. 1999); N.T. Wright, The New Testament and the People of God (Minneapolis: Fortress, 1992); Jesus and the Victory of God (Minneapolis: Fortress, 1996); The Resurrection of the Son of God (Minneapolis: Fortress, 2003). For a critique of Wright’s work, see C.C. Newman, Jesus & the Restoration of Israel: A Critical Assessment of N. T. Wright’s Jesus & the Victory of God (Downers Grove IL: IVP Academic. 2009); J.M. Scott, Exile: A Conversation with N.T. Wright (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic. 2017).

[12] Matt. 10:5-6; 15:24.

[13] M.W. Goheen, A Light to the Nations: The Missional Church and the Biblical Story (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker, 2011), 81.

[14] D.H. Stern, Restoring the Jewishness of the Gospel: A Message for Christians (Clarksville, MD: Lederer Books. 2010), Kindle Locations, 963 of 1967.

[15] Charlesworth, 46-47.