Editor’s note: This post originally appeared on Think Apologetics. Tabernacle of David considers this resource trustworthy and Biblically sound.

.

Introduction

Obviously, one of the most challenging issues within Christian apologetics is the accusation that in many cases, Christianity has been associated with anti-Semitism. Several years ago, I remember reading Lee Strobel’s book The Case for Faith. In one chapter he interviews John Woodbridge about Christian history. Woodbridge agreed that “One of the ugliest blights on Christianity’s history has been anti-Semitism.” Woodbridge readily conceded that, regrettably, “anti-Semitism has soiled Christian history”(The Case for Faith, pg 297).

There have been numerous books written on this topic such as Dan Cohn- Sherbock’s The Crucified Jew: Twenty Centuries of Christian Anti-Semitism, and Susannah Heschel’s The Aryan Jesus: Christian Theologians and the Bible in Nazi Germany as well as Michael Brown’s Our Hands Are Stained with Blood. I know Christians sometimes can say “How in the world could any Christian be anti-Semitic? Ronald Diprose says the following: “Whoever denies that Jesus is Israel’s Messiah is in fact denying the gospel which was announced to Abraham (Galatians 3:8–16; Romans 1:1–5, 16–17)” (see Israel and the Church: The Origins and Effects of Replacement Theology, by Ronald Diprose, pg 182).

When a Christian or someone is accused of being anti-Semitic, we can break it down into these three categories:

1 Anti-Semitism can be based on hatred against Jewish people because of their group membership or ethnicity.

2. Anti-Zionism is criticism or rejection of the right of Jewish people to have their own homeland. I should note that not all Jewish people are supportive of modern Zionism. Also, Christians are divided on this issue.

3. Theological anti-Semitism: critical rejection of Jewish principles and beliefs.

I should also note that the Jewish community has at least three ideas that most, if not all, Jewish people have been socialized into:

(1) The Holocaust – to deny the Holocaust is to remove oneself from the Jewish people.

(2) The State of Israel – its right to exist and some allegiance to it.

(3) The rejection of Jesus.

Of course, many Jewish people don’t know why part of their identity is to reject Jesus as their Messiah. But the history of anti-Semitism has been a huge stumbling block.

Sadly, some very well-known Christian leaders such as John Chrysostom (Against the Jews. Homily 1) and Martin Luther’s The Jews and Their Lies contain statements that can be perceived as fitting into one of the anti- Semitic categories that were just mentioned.

Anti-Semitism is alive and well in many parts of the world. Given Israel is continually in the news. But why would a devout follower of Jesus care about Israel? As David Stern says:

“For years all the disciples of Yeshua (Jesus) were Jewish. The New Testament was entirely written by Jews (Luke being, in all likelihood, a Jewish proselyte). The very concept of a Messiah is nothing but Jewish. Finally, Yeshua himself was Jewish—was then and apparently is still, since nowhere does Scripture say or suggest that he has ceased to be a Jew. It was Jews who brought the Gospel to Gentiles. Paul, the chief emissary to the Gentiles was an observant Jew all his life. Indeed the main issue in the early Church was whether without undergoing complete conversion to Judaism a Gentile could be a Christian at all. The Messiah’s vicarious atonement is rooted in the Jewish sacrificial system; the Lord’s Supper is rooted in the Jewish Passover traditions; baptism is a Jewish practice; and indeed the entire New Testament is built on the Hebrew Bible, with its prophecies and its promise of a New Covenant, so that the New testament without the Old is as impossible as the second floor of a house without the first.”- David Stern, Restoring the Jewishness of the Gospel, Kindle Locations, 963 of 1967.

Israel’s Election

What does it mean to say Israel was elected? Scott Bader-Saye says:

“Election is the choice by one person of another person out of a range of possible candidates. This choice then establishes a mutual relationship between the elector and the elected, in biblical terms a “covenant” (berit). Election is much more fundamental then just freedom of choice in the ordinary sense, where a free person chooses to do one act from a range of possible acts. Instead, the elector chooses another person with whom she will both act and elicit responses, and then establishes the community in which these acts are done, and then promises that for which the election has occurred. The content of these practical choices is governed by Torah, but there could be no such coherent standards of action without prior context of election, the establishment of covenantal community, and the promise of ultimate purpose.”– (see Scott Bader-Saye, The Church and Israel After Christendom: The Politics of Election(Boulder CO: Westview Press, 1999), 31).

What was Israel elected to do?

1. Be a holy people (Deut. 7:6 [3x]); (Isa. 62:12; 63:18; Dan. 12:7)

2.Be a kingdom of priests (Exod. 19:6)

3. Be a redeemed people (Joshua 4:23-24)

4. Be a light to the nations (Isa. 60: 3)

5. Bring the Scriptures to the world: “To them were entrusted the oracles of God” (Rom 3:2)

6. Be the vehicle by which the Messiah will come into the world (Rom 15: 8-9).

We also need to remember Israel’s election was only because of the grace of God:

“For you are a people holy to the Lord your God. The Lord your God has chosen you to be a people for his treasured possession, out of all the peoples who are on the face of the earth. It was not because you were more in number than any other people that the Lord set his love on you and chose you, for you were the fewest of all peoples, but it is because the Lord loves you and is keeping the oath that he swore to your fathers, that the Lord has brought you out with a mighty hand and redeemed you from the house of slavery, from the hand of Pharaoh king of Egypt.”- Deut. 7: 6-8.

Supersessionism in Church History

Before I expand on R. Kendall’s Soulen’s The God of Israel and Christian Theology which has shown the long history of supersessionism in Church history, we should note that according to to Mary Boys, this idea of the church replacing the Jews in the divine economy has eight main features: the assertion that the revelation of Christ supersedes the revelation to Israel, that the New Testament fulfills the Old Testament, the church replaces the Jews as God’s chosen people, that Judaism is obsolete, the notion that postexilic Judaism was legalistic, assertions that the Jews did not heed the warning of the prophets and did not understand the prophecies about Jesus), and finally accusations that the Jews killed Christ. These might be thought of as the basic tenets of supersessionism (see “The Road to Reconciliation: Protestant Church Statements on Jewish-Christian Relations.” In Seeing Judaism Anew: Christianity’s Sacred Obligation, edited by Mary C. Boys ( Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. 2005), 241-251.

After the Holocaust, many Christian theologians had to rethink the relationship between the Church and Israel.

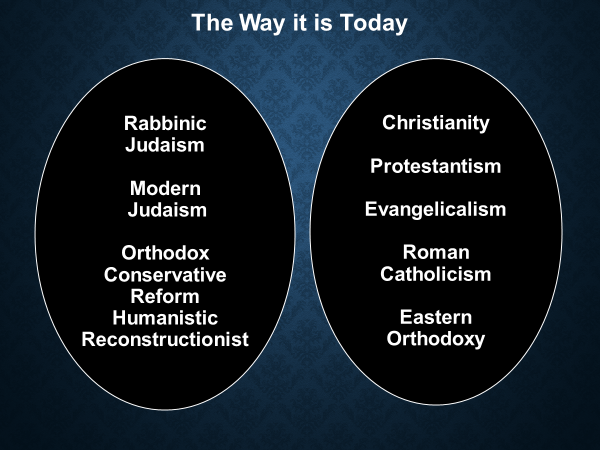

Supersessionism is sometimes seen as another word what is called “replacement theology,” “transference,” “expansion” “absorption” or “fulfillment theology.” The term supersessionism comes from two Latin words: super (on or upon) and sedere (to sit). It carries the idea of one person sitting on another’s chair, displacing the latter. Hence, one religion, Christianity, permanently displaces the other, Judaism. By the way, Islam is viewed as a new religion that ‘supersedes’ both Judaism and Christianity. Given I have already written a post on whether Jesus came to bring a new religion (i.e. Christianity), I won’t deal with that issue in great detail here. But suffice to say, it is fallacious for Christians to assume there was one clear Judaism in the first century—viewed through the lens of Paul’s critique of the law and represented by the Pharisees as depicted in Matthew—and then Jesus came along and started a new religion called ‘Christianity’ as a new entity that separated from Judaism. As Craig Evans says so well:

“Did Jesus intend to found the Christian church? This interesting question can be answered in the affirmative and in the negative. It depends on what precisely is being asked. If by church one means an organization and a people that stand outside of Israel, the answer is no. If by a community of disciples committed to the restoration of Israel and the conversion and instruction of the Gentiles, then the answer is yes. Jesus did not wish to lead his disciples out of Israel, but to train followers who will lead Israel, who will bring renewal to Israel , and who will instruct Gentiles in the way of the Lord. Jesus longed for the fulfillment of the promises and the prophecies, a fulfillment that would bless Israel and the nations alike. The estrangement of the church from Israel was not the result of Jesus’ teaching or Paul’s teaching. Rather, the parting of the ways, as it has been called in recent years, was the result of a long process. But we must ask if Paul has created a new institution, a new organization, something that stands over against Israel, something that Jesus himself never anticipated. From time to time learned tomes and popular books have asserted that the Christian church is largely Paul’s creation, that Jesus himself never intended for such a thing to emerge. Frankly, I think the hypothesis of Paul as creator of the church or inventor of Christianity is too simplistic. A solution that is fairer to the sources, both Christian and Jewish, is more complicated.” – Craig A. Evans, From Jesus to the Church: The First Christian Generation, pgs, 18, 36.

Here are some helpful illustrations:

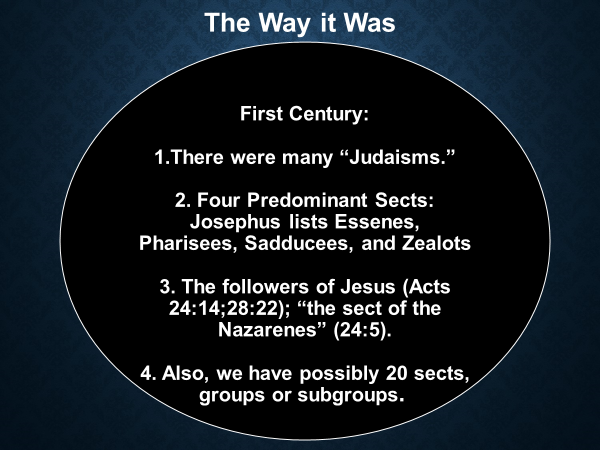

Linguistically speaking, Christianity didn’t exist in the first century. Judaism in the first century wasn’t seen as a single “way.” There were many “Judaisms”- the Sadducees, the Pharisees, Essenes, Zealots, etc. The followers of Jesus are referred to as a “sect” (Acts 24:14;28:22); “the sect of the Nazarenes” (24:5). Josephus refers to the “sects” of Essenes, Pharisees, Sadducees. The first followers of Jesus were considered to be a sect of Second Temple Judaism. Even James Dunn says the following:

“Prior to Paul what we now call ‘Christianity’ was no more than a messianic sect within first-century Judaism, or better, within Second Temple Judaism — ‘the sect of the Nazarenes’ (Acts 24.5), the followers of ‘the Way’ (that is, presumably, the way shown by Jesus)”- James Dunn, Jesus, Paul and the Gospels, pg 119

The title “replacement theology” is often viewed as a synonym for supersessionism. As of today, because the title “replacement theology” is not well received by some, some scholars/theologians prefer to be called “fulfillment theologians.” Thus, the emphasis is on the “promise/fulfillment” theme in the Bible. However, while one can use fulfillment terminology, the end the result is really the same— we see the following:

Israel, the “earthly” people of God in the Old Testament, which includes their land, temple, and identity as an ethnic or national people, has been replaced, expanded, or fulfilled in the divine plan not by another “earthly” people or peoples, but by a “spiritual” people, the church of the New Testament.

As I just mentioned, a leading voice in this issue is R. Kendall Soulen, Professor of Systematic Theology at Wesley Theological Seminary, Washington DC. Soulen’s theological project is to reconceive the standard Christian “canonical narrative”—i.e., our view of the Bible’s overarching narrative framework—in such a way that avoids supersessionism and consequently is more coherent. Soulen identifies three kinds of supersessionism: (1) economic supersessionism, in which Israel’s obsolescence after the coming of the Messiah is a key element of the canonical narrative, (2) punitive supersessionism, in which God abrogates his covenant with Israel as a punishment for their rejection of Jesus, and (3) structural supersessionism, in which Israel’s special identity as God’s people is simply not an essential element of the “foreground” structure of the canonical narrative itself. Soulen sees structural supersessionism as the most problematic form of supersessionism, because it is the most deep-rooted.

He identifies structural supersessionism in the “standard model” of the canonical narrative, which has held sway throughout much of the history of the Christian church. This standard model is structured by four main movements: creation, fall, Christ’s incarnation and the church, and the final consummation. In this standard model, God’s dealings with Israel are seen merely as a prefigurement of his dealings with the world through Christ. Thus, the Hebrew Scriptures are only confirmatory; they are not logically necessary for the narrative (see Lionel Windsor’s Reading Ephesians and Colossians after Supersessionism: Christ’s Mission through Israel to the Nations (New Testament after Supersessionism Book 2)

Economic Supersessionism

In this view, Israel is not replaced primarily because of its disobedience but rather because its role in the history of redemption expired with the coming of the Messiah. It is now superseded by the arrival of a new spiritual Israel, the Christian church. Thus, Israel was never in God’s mind more than a temporary reality ultimately to be superseded by “a new Israel,” the church.

Thus, the ethnic, national, and territorial promises to Israel have to be spiritually interpreted in order to discern their true meaning.

In his book Israel in the Apostolic Church, Peter Richardson notes that Justin Martyr (100 – 165 AD), an early Christian apologist, was the first Christian writer to explicitly identify the church as “Israel.” Justin declared, “For the true spiritual Israel, and descendants of Judah, Jacob, Isaac, and Abraham . . . are we who have been led to God through this crucified Christ.”.He also said, “Since then God blesses this people [i.e., Christians], and calls them Israel, and declares them to be His inheritance, how is it that you [Jews] repent not of the deception you practice on yourselves, as if you alone were the Israel?. Justin also announced that “we, who have been quarried out from the bowels of Christ, are the true Israelite race”(See Justin, Dialogue with Trypho 11, ANF 1:200. 17. Ibid., 1:261; 18. Justin, Dialogue with Trypho 135, ANF 1:267).

In my experience, when I have brought up Richardson’s work about Matyr, Christians can immediately get defensive and attempt to point to all kinds of texts in the New Testament that seem to teach economic supersessionism or fulfillment theology.

Israel in the Scriptures

Now when we say “Israel” we have to define what we mean. Do we mean Israel the land, Israel the people, or the government of Israel? We know that Jacob experienced a theophany and was given a new name (Yisrael) meaning he had persisted with God. There are 15 references to Jacob’s children as the sons of Israel (b’nai yisrael) (Gen 45:21; 46:8; 50:25; Exod. 1:1; 13:19; 28:9; 11-12; 21, 29; 39:6-7,14; Deut. 32:8;1 Chron.2:1). Israel is national name that is used when they were delivered by God for Egyptian bondage (Exod. 1:9; 12; 2:23; 25) and for those who came out afterward (Exod. 10:5-6). Israel is also seen as a political entity or nation state (1 Sam.15;28; 24;20; 1 Chron.11:10); the royal monarchy under the rule of David, Saul and then his descendants.

The ethnic origin of Israel as expressed in the concept of “people,” can be traced back to Abraham (cf. Ge 12:2; 17:6; 18:18). “Israel” is used seventy-three times in the New Testament, and it is always used of ethnic Jews. Thus, of these seventy-three citations, the vast majority refer to national, ethnic Israel. The passages that are generally disputed are the “Israel of God” reference in Galatians 6:16 and Romans 9:6 which both speak of a believing remnant within Israel. Thus, there is an ‘Israel’ within ethnic ‘Israel.’ But neither of these texts teach Gentiles become spiritual Jews.

Even in Acts, after the title “church” (ἐκκλησία/ekklēsia) is established, Israel is still addressed as a nation in contrast to Gentiles (Acts 3:12; 4:8, 10; 5:21, 31, 35; 21:28). Sometimes, it is asserted that the imagery for Israel is used for the “church”/ekklēsia. Perhaps, like Israel, if the ekklēsia. are “a people that are his very own” (Tit 2:13; Ex 19:5; Rom 9:25; 2 Co 6:16; . 1Pe 2:9–10), they are now called “Israel?”

However, to assume just because the “people of God” has been enlarged to include those from nations other than Israel means that the ekklēsia is now Israel leads to some exegetical problems. For example, in 1 Peter 2:9–10, was Peter was addressing Gentile believers in his epistle or was it written to Jewish Believers in the Diaspora? If it was written to Jewish Believers, Peter could be addressing a similar group Paul was referring to in Gal 6:16—a remnant of Israel made of ethnic Jews who placed their faith in the Messiah. Other texts that are somtimes used to demonstrate that the the church is the fulfillment of Israel or the “true Israel” are Rom. 2:28–29; 4:11–12; 9:6–8; Gal. 3:16–29 and Eph. 2:11–22. However, these texts are disputed as well. Of course, there is no text that says the church is the “true Israel.” As seen above, Matyr was the first person to assert the church is the “true Israel.” In most cases, inferences are made from the texts that have just been mentioned. One way or the other, there is no possibility anyone should be able to infer from any of these texts that Israel has been irrevocably rejected by God and replaced by Gentiles (see Rom. 9–11).

Furthermore, what can be forgotten is that though when most Christians hear the word “church” they assume this means “Christian church,” the reality is that in the first century, “ekklēsia” could refer to synagogue institutions, public assemblies or what our English translations refer to as “assembly.”

As I have already said, to assume there is an actual Christian church that is outside the Jewish world is to read our modern understanding or ecclesiastical tradition back into the first century.

I should also note that Philippians 3: 3 is another text that is seen as supporting the ekklēsia as being Israel. The NASB translates it as “for we are the true circumcision, who worship in the Spirit of God and glory in Christ Jesus and put no confidence in the flesh.” (NASB) Unfortunately, the word “true” isn’t in the Greek text. Phil 3:3 simply refers to those Jews and Gentiles circumcised in their hearts in the new covenant. In the new covenant, both Jew and Gentile who follow the Messiah may experience circumcision of the heart and are spiritually “one in Messiah” (Gal 3:28). Thus, both Jew and Gentile can have a heart that can be circumcised!

Jesus as the True Israel?

Another place where economic supersessionism is apparent is the common saying that “Jesus is the true Israel.” I see this come up a lot. In this view, in the idea of corporate solidarity, one person can represent a whole group. In other words, Jesus as the Messiah is the culmination of the characteristics within the positions. Given the Messiah is the ideal representative of his people (Israel), Jesus as their head, is seen as Israel! Another way to view this is if our current president went to meet the leadership of Russia and he said, “I am the United States.” In other words, he is saying the president is the head of the country.

Some examples are the following: Since Israel is a son of God (corporately), Jesus is the ideal “Son of God/The Davidic King. Or, as Israel is called to be “ a kingdom of priests and a holy nation( Exod. 19:5-6), Jesus, as their ideal representative fulfills the role of priest, as being exalted to a permanent priesthood by his resurrection and enthronement at the right hand of God in the heaven (Hebrews 8:1). Or, as Israel is the Servant of the Lord and Jesus is the Servant of the Lord, He embodies everything Israel was called to be and do! Some of the passages about the Servant of the Lord are about the nation of Israel (Is.41:8-9; 42:19; 43:10; 44:21; 45:4; 48:20), while there are other passages where the Servant of the Lord is seen as a righteous individual (Is.42:1-4;50:10; 52:13-53:12).

Granted, no New Testament author ever calls Jesus “Israel” or “True Israel.” The real question is whether Jesus is called to ‘restore’ Israel, or ‘absorb’ Israel. Is he called to fulfill (which sadly, translates as ‘end’ as many Christians see it) everything about Israel? Remember as Evans just said:

“Jesus did not wish to lead his disciples out of Israel, but to train followers who will lead Israel, who will bring renewal to Israel , and who will instruct Gentiles in the way of the Lord. Jesus longed for the fulfillment of the promises and the prophecies, a fulfillment that would bless Israel and the nations alike. The estrangement of the church from Israel was not the result of Jesus’ teaching or Paul’s teaching. Rather, the parting of the ways, as it has been called in recent years, was the result of a long process”—Craig Evans , From Jesus to the Church: The First Christian Generation.

Even if Jesus did demonstrate he was the corporate head of Israel, to say this means He has “replaced” “expanded” or “fulfilled” or “ended” Israel’s role as the “earthly” people of God (which includes their land and identity as an ethnic or national people), takes some serious exegetical work.

In Jeremiah 31:35–37, God links Israel’s perpetual existence as “a nation” with the sun, moon, stars, and foundations of the earth. With Romans 9:4–5 Paul explicitly affirms that the “covenants,” “promises,” and “temple service” still belong to national Israel, even when Israel as a whole was characterized by unbelief. The context makes it clear that Paul is speaking of Israel in unbelief. Michael Rydelnick points out the following:

“ In Rom. 9:1–3 the apostle makes plain his compassion and concern for the lost condition of his unbelieving brethren. So great was his love that he makes the remarkable statement that he would be willing to be accursed and separated from the Messiah, if this could provide spiritual life for his people. There is no question that Paul is speaking of unbelieving Israel here. Nevertheless, he describes them as having a significant national status: “They are Israelites, and to them belong the adoption, the glory, the covenants, the giving of the law, the temple service, and the promises. The ancestors are theirs, and from them, by physical descent, came the Messiah, who is God over all, praised forever. Amen” (HCSB). The present tense verb in verse 4 demonstrates that all the benefits described still belong to Israel. As Thomas Schreiner writes, “The present tense verb εισιν (eisin, they are) indicates that the Jews still ‘are’ Israelites and that all the blessings named still belong to them.” (see Thomas R. Schreiner, Romans, Baker Exegetical Commentary on the New Testament (Grand Rapids: Baker Books, 1998).

Of these benefits that God has granted to Israel, two are significant to this discussion. The Jewish people still have covenants and promises to claim, both of which include God’s grant of a specific territory. There is no way to separate the territorial promises found in the covenants or to think that Paul now views them as belonging to an alleged new spiritual Israel (the Church). Nor did he mean that these promises have been expanded to refer to the whole world and not the land of Israel. It seems Paul still believes that the God of Israel has granted the people of Israel covenants and promises, and thus that God has given them a specific territory. The third crucial passage reaffirming Israel’s covenant status is Romans 11:28–29: “Regarding the gospel, they are enemies for your advantage, but regarding election, they are loved because of the patriarchs, since God’s gracious gifts and calling are irrevocable. Here are three observations to be derived from these verses. First, Paul is speaking of Israel in unbelief, a reference to the Jewish people who, for the most part, are opposed to the gospel.

This does not mean that all Jewish people are clinging to unbelief as Paul has already identified a remnant of faithful Jewish people (Rom. 11:1–5) who are followers of Jesus. Nevertheless, the majority of Jewish people do not believe Jesus is the promised Messiah. God used this in an advantageous way for the Gentiles as Jewish nonbelief has mysteriously led to the gospel spreading to the Gentile world (Rom. 11:11). Second, the Jewish people remain God’s chosen people. The word “election” used here means “chosen.” Therefore, the NASB translates it as “from the standpoint of God’s choice,” indicating that the Jewish people remain chosen (see the chapter called “The Hermeneutics of Conflict” in Israel, the Church, and the Middle East, by Darrell L. Bock, Mitch Glaser).

Gentile Inferiority?

I can only reflect on my own experience. That means I don’t speak for everyone. But I have seen a lot of Gentiles who simply don’t understand the election of Israel or feel they are inferior to Israel. With the coming of the Messiah, I have no idea why this continues to happen. One passage that continually gets misinterpreted is Gal 3: 26-29: “For in Christ Jesus you are all sons of God, through faith.For as many of you as were baptized into Christ have put on Christ.There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave[ nor free, there is no male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus. And if you are Christ’s, then you are Abraham’s offspring, heirs according to promise” (ESV).

I have seen many Christians assume this text is saying God has wiped out all ethnic distinctions. But all one must do is read it in context. For that matter, a rule of thumb is to never ignore the immediate context and the wider context. Thus, we would have to look at all the passages that discuss the issue. Obviously, if we read it in context and assume God has wiped out all ethnic distinctions, than males aren’t males anymore and females aren’t females. With the coming of the Jewish Messiah, spiritually speaking, Gentiles are equal with believing Jewish people. But we see Paul goes onto to speak of Jews and Gentiles as distinct ethnic groups in his letters (Rom. 1:16; 9:24; 1 Cor. 1:24; 12:13; Gal. 2:14, 15). Paul expresses the relationship of Gentiles to Jews/Israel by saying Gentiles are “fellow citizens” (Eph. 2:19), “joined together” (Eph. 2:21), “built together” (Eph. 2:21), “heirs together” (Eph. 3:6), “members together of one body” (Eph. 3:6), as well as “sharers together” (Eph. 3:6). The Gentiles are brought near to Israel in the Jewish Messiah to share with Israel in its covenants, promise, hope, and God. But they do not become Israel; they share with Israel. So when looking at individual salvation, there is neither Jew nor Gentile (Galatians 3:28), no distinction between them (Romans 10:12), no dividing wall of hostility (Ephesians 2:14-19). But being unified as one in the Messiah does not nullify functional distinctions.

This should be no surprise given that the Abrahamic covenant was to not only bless Israel, but the the Gentile groups of the world (Gen. 12:2–3; 22:18). The original words “goyim” and “ethnos” refer to “peoples” or “nations” and are applied to both Israelites and non-Israelites in the Bible. The Jewish Scriptures had already revealed that Gentiles will be restored to God as a result of Israel’s end-time restoration, and will become united to them (Psalms 87:4-6; Isa. 11:9-10; 14:1-2; 19:18-25; 25:6-10; 42:1-9; 49:6; 51:4-6; 60:1-16; Jer. 3:17; Zeph. 3:9-10; Zech. 2:11). In the Tanak (Old Testament) even though non-Jewish people could become part of the commonwealth of Israel as proselytes, the physical element is never abolished. Non-Jewish people were already seen as were seen as joining themselves to the Lord as “others,” rather than joining Israel through conversion. A clear distinction between Israel and the nations is seen in Isaiah 56:6; Micah 4:2. Thus, nations could become part of Israel, but they worship God as foreigners because God’s house is now a house of prayer for all peoples (Isa. 56:7).

Even at the “Jerusalem Council” in Acts 15 the conclusion was God had accepted the Gentiles as Gentiles in accordance with a prophecy (Amos 9:11, 14), and also of “all the nations who are called by my name” (Amos 9:12). God’s work among Gentile believers in Jesus by the Holy Spirit shows Gentiles don’t become Jews nor even spiritual Jews (Acts 15:8–17a; cf., 11:1–18).

The Challenge of Systematic Theology

There is no doubt that the debate about the role of Israel in the Bible has been debated primarily by two theological systems: Dispensationalism/Progressive Dispensationalism and Covenantal Theology. Both camps have made several modifications in their views. Having read quite a bit of literature on the topic myself, I have seen this debate for many years now. If you like systematic theology, these are the two main choices. But for many scholars, they tend to think that trying to start with a system and then to try to make the Bible fit into a school of thought can be a risky endeavor. After all, the Bible isn’t a systematic theology. Rather, we take the Bible and make into a systematic theology. Then we can spend our lives defending our systems. When the Bible was written, obviously, no author was familiar with many of the modern systematic theologies that are taught in Christian seminaries. It is not as if they sat around arguing about whether Ἰσραήλ “Israel” is the “church” (ἐκκλησία/ekklēsia). Let me give an example by looking at Matthew’s Gospel where he mentions both the church and Israel.

Matt 2:6 And you, Bethlehem, in the land of Judah, are by no means least among the leaders of Judah: because out of you will come a leader who will shepherd My people Israel.

Matt 2:20 saying, “Get up! Take the child and His mother and go to the land of Israel, because those who sought the child’s life are dead.”

Matt 2:21 So he got up, took the child and His mother, and entered the land of Israel. Matt 8:10 Hearing this, Jesus was amazed and said to those following Him, “I assure you: I have not found anyone in Israel with so great a faith!”

Matt 9:33 When the demon had been driven out, the man spoke. And the crowds were amazed, saying, “Nothing like this has ever been seen in Israel!”

Matt 10:6 Instead, go to the lost sheep of the house of Israel.

Matt 16: 18 And I tell you, you are Peter, and on this rock I will build my church, and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it

Matt 18:17 If he pays no attention to them, tell the church. But if he doesn’t pay attention even to the church, let him be like an unbeliever and a tax collector to you.

So is Matthew saying Ἰσραήλ “Israel” is the same thing as the “church” (ἐκκλησία/ekklēsia)?

Fortunately, scholars are working on new paradigms which should help with this discussion. But Christians like labels and old paradigms don’t easily die. There is a group of scholars working on post-supersessionist thought.

In a future post, I will discuss the over reaction to the dispensationalism camp/Left Behind Series pop eschatology as well. But perhaps we can ponder this question: if someone does hold to holds to economic supersessionism, does this mean they are anti-Semitic? I would say it depends on the individual. I have encountered Christians who quote texts to try to prove their point about the Church superseding Israel. Some of them are quite aggressive and some make some very anti-Semitic comments. But even though economic supersessionism was endorsed by people such as Matyr, Tertullian, Origen, St. Hillary, St. Ambrose, St. John Chrysostom, St. Jerome, St. Cyril of Alexandria, St. Prosper of Aquitaine, Cassiodorus, Preniasius, St. Gregory the Great, St. Isidore, Venerable Bede, St. Anselm, St. Peter Damian, and St. Bernard and others, what is ironic is that many of these same figures believed in a future salvation or even restoration of Israel. I will define these issues more clearly in our next post.

Even though popular or modern theologians such as Wayne Grudem and Millard Erickson hold to a economic supersessionism, they also affirm a future for Israel. As Grudem says:

Many New Testament verses . . . understand the church as the ‘new Israel’ or new ‘people of God.’” Yet he also says: “I affirm the conviction that Rom. 9–11 teaches a future large-scale conversion of the Jewish people” (see W. Grudem, Systematic Theology: An Introduction to Biblical Doctrine (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1994), 861).

Erickson says:

“To sum up then: the church is the new Israel. It occupies the place in the new covenant that Israel occupied in the old. . . . There is a special future coming for national Israel, however, through large-scale conversion to Christ and entry into the church.” He also says, “There is, however, a future for national Israel. They are still the special people of God” (see Milliard Erickson, A Basic Guide to Eschatology (Grand Rapids: Baker. 1998), 123-124.

Or, you can see the long history of interpretation of Romans 11:26. here. It shows how many ancient and modern commentators have viewed Israel in that text.

In the next post, we will discuss structural supersessionism.