Editor’s note: This post originally appeared on Think Apologetics. Tabernacle of David considers this resource trustworthy and Biblically sound.

.

For the last fifteen years I have done campus apologetics. Thus, I have heard my share of objections to God’s existence. I have lost count of the number of times I have heard comments such as “You can’t prove God’s existence” or “We can’t be certain there is a God,” or, “I don’t think we can know God exists.” The list goes on and on. I have run into my share of people who think they need to be absolutely certain of God’s existence and that Jesus is His Son. Most recently, two Christians critiqued William Lane Craig’s article in the New York Time about God’s existence. They don’t like any claim that says we aren’t absolutely certain about the truthfulness of our faith. What is this really all about? It is about what is called Religious Epistemology. I was blessed to be able to take a graduate level class on this topic in seminary. I don’t claim to be an expert. But I have learned some of the basics. Here are some of the terms help with these discussions:

I. Epistemology: Is the branch of philosophy concerned with questions about knowledge and belief and related issues such as justification, truth, types of certainty.

a. Justification: a belief is said to be justified when a person fulfills his or her duties in acquiring and maintaining a belief. A belief is said to be justified when it is based on a good reason/reasons or has the right grounds or foundation.

b. Knowledge: Knowledge is a belief that is true and warranted or properly accounted for. In other words, knowledge excludes beliefs that are just true accidentally.

Example: It is 12:30 pm and through an antique shop window I happen to look at a non-working clock, which happens to indicate 12:30. I would not be warranted in concluding that it’s 12:30 P.M. I may have belief that is true- the first components of knowledge—but I happened to get lucky. That does not qualify as knowledge; it’s not properly warranted (which completes the definition of knowledge). NOTE: This example was taken from Paul Copan’s True for you, but not for me: Deflating the Slogans that Leave Christians Speechless.

Also: All possible knowledge depends on the validity of reasoning. Is mind the product of matter—more precisely, an accidental by-product of blind material forces of nature? From an evolutionary perspective, it doesn’t matter whether an organism has true beliefs, false beliefs, or no beliefs at all, as long as the organism can effectively preserve and pass on its genes. Evolution isn’t truth-directed. It’s only survival-directed. (James Anderson, Why Should I Believe Christianity? (The Big Ten) (Scotland: Christian Focus Publications, 2016), Kindle Locations 1178 of 2480).

Common Sense Beliefs: Beliefs we take for granted in the common concerns of life, without being able to give a reason for them:

a.Testimony: We rightly accept what others tell us without having first established that they are worthy of trust. Without testimony, we could never be able to learn a language or accept something we learned before checking out for ourselves.

b.We trust our senses on a daily basis/we trust our cognitive faculties. We rely on introspection, intuition, and perception on a daily basis.

c. Memory: Memory is a pervasive, bedrock of our intellectual existence.

Skepticism and God’s Existence:

Strengths of Skepticism:

a. Skepticism can be healthy and constructive. After all, we shouldn’t be gullible and naïve, believing everything we hear or read.

b. Religious/Revelatory Claims are contradictory: We are required to provide reasons and evidence for what we believe.

Weaknesses of Skepticism: (NOTE: Points a-e are adapted from How Do You Know You’re Not Wrong? A Response to Skepticism by PaulCopan).

a. Skeptics are more skeptical about religious beliefs that anything else!

b. Skeptics aren’t truly skeptical about two fundamental things they take for granted: (a) the inescapable logical laws that they’re constantly using to disprove the claims of those who say they have knowledge or (b) that their minds are properly functioning so that they can draw their skeptical conclusions!

c. Being less than 100% certain doesn’t mean we can’t truly know. We can have highly plausible or probable knowledge, even if it’s not 100% certain.

d. The skeptic does not realize we don’t have to have absolute certainty to know something; we know many things that we aren’t absolutely certain about, and this is legitimately called “knowledge.”

e. The hyper-skeptic is in a position that ends up eliminating any kind of personal responsibility or accountability.

f. Skeptics need to be clear about what kind of approach they are taking to the existence of God (i.e., religious experience, induction, deduction, a historical approach, empirical approach, inference to the best explanation, etc).

Deduction, Induction, and Abduction

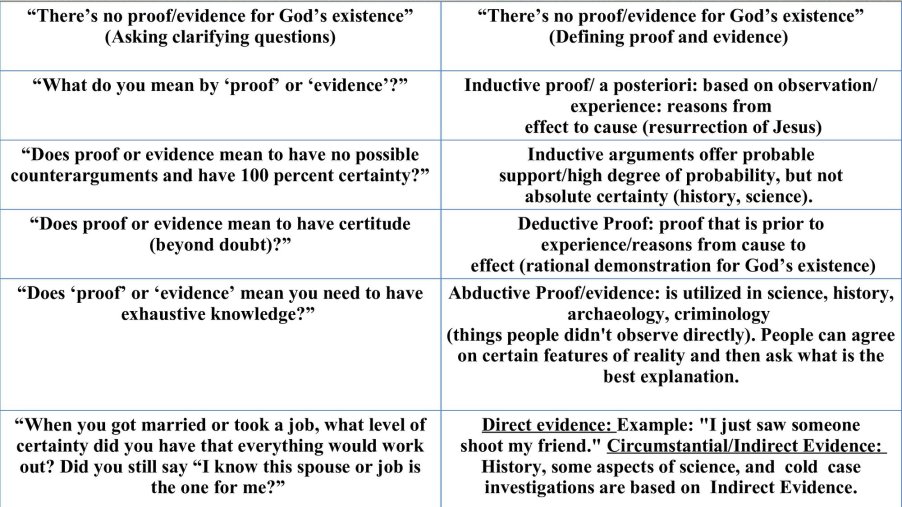

When someone tells me I have not proven God’s existence, I ask them if they know the difference between deduction, induction, and abduction. You may say ‘well, you are using big words.” But look at our chart here:

Deductive Arguments: In a deductive argument, the premises are intended to provide support for the conclusion that is so strong that, if the premises are true, it would be impossible for the conclusion to be false.

(Premise 1)…….All the books on that shelf are science books.

(Premise 2)…….This book is from that shelf.

(Conclusion)……This book is therefore a science book.

You might say, well what kind of deductive arguments are there for God’s existence. I would suggest reading Edward Feser’s Five Proof’s For The Existence of God.

Yes, it is true that nobody needs to master these arguments to find God. But they are still important.

Inductive Arguments: In an inductive argument, the premises are intended only to be so strong that, if they are true, then it is unlikely that the conclusion is false.

(Premise 1)…….This book is from that shelf.

(Premise 2)…….This book is a science book.

(Conclusion)……All the books on that shelf are science books.

In this argument, even if the premises are true, you could not conclude, with certainty, that all of the books on the shelf are science books just from the two pieces of information given in the premises.

Now, when it comes to inductive proofs (as seen in the chart above), we can only arrive at probability levels. This happens in science as well. This may make people uncomfortable. But that’s the way it is.

Remember, probability comes in degrees

a. Virtual Certainty: Where the evidence is overwhelmingly in its favor( the law of gravity)

b. Highly probable: Very good evidence in its favor (There was a man named Jesus who lived 2,000 years ago and was crucified)

c. Probable: Means there is sufficient evidence in its favor (Paul wrote Galatians and 1 Corinthians)

d. Possible: Seems to have evidence both for and against (The Shroud of Turin is the cloth that covered Jesus when he was in the tomb)

e. Improbable: Insufficient Evidence in its favor (Life can come from non-life)

f. Highly Improbable: Very little evidence in its favor (The events in the Book of Mormon took place)

Abduction: Inference to the Best Explanation

We don’t have direct evidence for the events in the Bible. But remember we don’t have direct evidence for many events that are in the past that lead to scientific conclusions. Almost all historical inquiries as well as cold case investigations are built on indirect or what is called “circumstantial evidence.” A large majority of science, history, and cold case investigations involve making inferences. Historians collect the data and draw conclusions that provide the best explanation that covers all the data in what is called “Inference to the most reasonable explanation” which never leads to absolute certainty or exhaustive knowledge. Mathematical propositions like 2+2=4 are absolutely certain by most people (except for a few philosophers maybe); such certainty is at times required for the resurrection question by skeptics. The process of finding the best explanation involves applying standards such as explanatory power and scope to the different theories on offer. Explanatory power is how well an explanation explains; explanatory scope is how much an explanation explains. While some skeptics will say they don’t absolute certainty for the resurrection of Jesus, many people choose to stay in a stubborn agnosticism simply because they claim they haven’t found the level of certainty that they need.

Remember that many people make major commitments in life based on probable knowledge. When you get married or take a job or make other life commitments, you may have unanswered questions, gaps of knowledge, or levels on uncertainty. But you still make major commitments. You say “I know this is the right choice!” Why do some people have to have every question answered before making a commitment to God or Jesus? I think it is because it involves their autonomy.

Kinds of Certainty

a. Mathematical Certainty: ( 7+5+12)

b. Logical Certainty: (There are no square circles)

c. Existentially Undeniable: ‘I exist’

d. Spiritual (Supernatural) Certainty: ‘I experience the Holy Spirit in my life’

e. Historical Certainty: Since history and science is mostly inductive, we can only arrive at probabilities

f. Pragmatic certainty: If something works or has beneficial consequences. This is challenging since someone could believe something works that does not correspond to reality.

Remember, a Christian can claim to arrive at “spiritual or supernatural certainty” because of the work of the Holy Spirit. That is fine. But that is not a public claim. It is a private and internal experience.

If you haven’t purchased the book Doubting Toward Faith

“Here’s a thought to digest: In the absence of certainty, there’s always room for doubt. And this applies not only to the Christian but to everyone. No one, in any belief system, can prove his or her faith with 100 percent certainty. But 100 percent certainty is also not required in order to believe in something or to have reasonable assurance that what you believe is true and trustworthy. • I believe my wife when she says she’ll be faithful to only me. • I believe my friends when they say, “I’m telling you the truth.” • I believe the red light will turn green in a reasonable amount of time. • I believe my government won’t collapse tomorrow.

But Bobby, I feel 100 percent certain that Christianity is true,” you may contest. And I would add, we cannot confuse feeling certain and being certain. There’s a difference. Mormons also feel certain their beliefs are true, as do Muslims, atheists, and many others. Feeling certain and being certain aren’t necessarily equivalent. As we all know, feelings are fickle. One day your moods may sing the praises of your faith and the next day your moods will betray you, drowning you in the despair of doubt. Many people who walk around saying “I know with 100 percent certainty that my faith is true” haven’t thought much about their faith. They’re often blissfully naïve, which insulates them from an onslaught of doubts.The reality is, even those who feel 100 percent certain can’t prove Christianity with 100 percent certainty. And we do the church a great disservice when we act like we can. Not to mention, we also set new believers up for a future doubt crisis when they realize things in our faith aren’t as tidy as they once thought. In any event, we must avoid two extremes, this time as it relates to certainty. On one extreme we have philosophers like René Descartes who seek certainty through doubting everything, and on the other extreme are those who doubt nothing in order to feel good about their supposed certainty. Neither solution is helpful.”

A Christian could claim that they have absolute certainty regarding the historical evidence for the resurrection. Bur this is incorrect. We can only make inductive and abductive claims about history. A Christian could also claim to have pragmatic certainty. But guess what? What kind of certainty do you have when Christianity doesn’t work?

What is Certitude, Doubt, and Beyond A Reasonable Doubt?

Certitude

In order for a judgment to belong in the realm of certitude, it must meet the following criteria:

(1) It cannot be challenged by the consideration of new evidence that results from improved observation

(2) It can’t be criticized by improved reasoning or the detection of inadequacies or errors in the reasoning we have done. Beyond such challenge or criticism, such judgments are indubitable, or beyond doubt.

Doubt

A judgment is subject to doubt if there is any possibility at all (1) of its being challenged in the light of additional or more acute observations or (2) of its being criticized on the basis of more cogent or more comprehensive reasoning.

Beyond a Reasonable Doubt

A courtroom analogy is helpful here: a jury is asked to bring in the verdict that they have no reason to doubt- no rational basis for doubting- in light of all the evidence offered and the arguments presented by the opposing counsel. Of course, it is always possible that new evidence may be forthcoming and, if that occurs, the case may be reopened and a new trial may result in a different verdict. The original verdict may have been beyond a reasonable doubt at the time it was made, but it is not indubitable-not beyond all doubt or beyond a shadow of a doubt–precisely because it can be challenged by new evidence or set aside by an appeal that called attention to procedural errors that may have invalidated the jury’s deliberations- the reasoning they did weighing and interpreting the evidence presented. NOTE: This was adpated from Mortimer Adler’s Six Great Ideas.

How many of our beliefs are based on certitude? Not many!

I hope these terms help in your discussions about God.